Source: https://www.livemint.com/mint-top-newsletter/easynomics11032022.html

Prefer audio? Now you can listen to your favourite newsletter.

Johann von Goethe’s novel The Sorrows of Young Werther is the story of a young man who has fallen in love with a woman engaged to another man. As Robert H Frank writes in Under the Influence—Putting Peer Pressure to Work: “The anguish provoked by unrequited love eventually becomes more than the young Werther can bear, and in the end, he takes his own life.”

The novel was published in 1774 and received widespread critical acclaim. Nonetheless, in the years that followed, a wave of suicides swept Europe. As Frank writes: “Investigators discovered that many of the victims had been strongly influenced by Goethe’s narrative. Suicide had become a meme.” Goethe’s novel was later banned in several regions across Europe to stem the imitative suicides.

This is an extreme example. Nonetheless, we humans do end up imitating what people around us are doing. And when a sufficient number of people imitate what others around them are doing, we end up in a situation referred to as a herd mentality.

Following others mindlessly might sound like a stupid thing to do, but that’s not always the case. In Money in One Lesson, Gavin Jackson writes: “Getting information from other people’s behaviour is not stupid. Most of us have to deal with situations where we do not have all the information and have to rely on rules of thumb.”

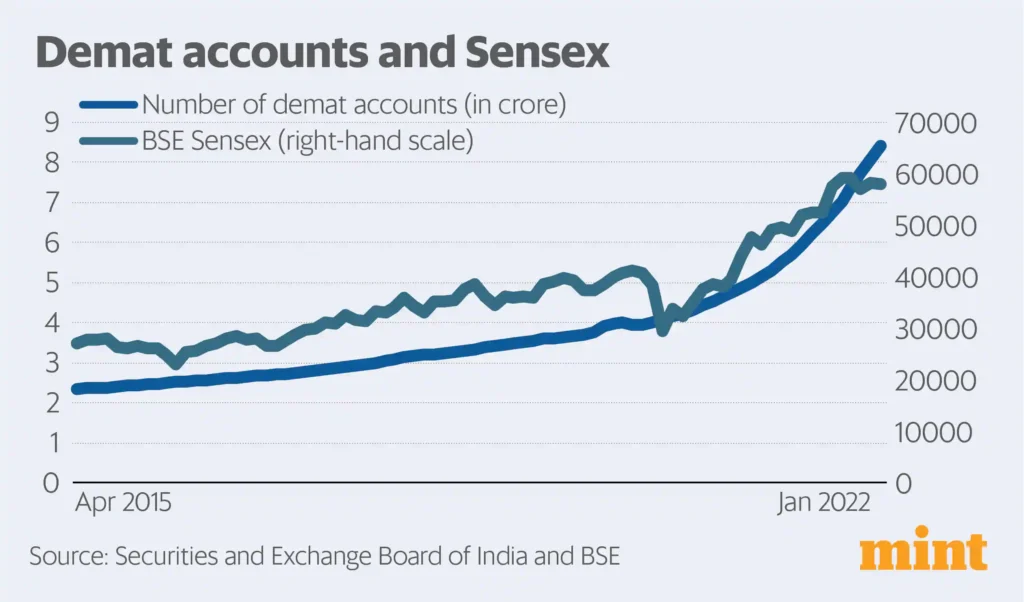

Take a look at the following chart.

Why has this happened? The simplest answer is herd mentality. Individuals have seen people around them make money by investing in stocks. This and the fear of missing out have gotten more people to open a demat account. More demat accounts being opened means that as stock prices have gone up from April 2020 onwards, it has led to a flood of retail money being invested into stocks.

Of course, those who opened demat accounts in 2020 and early 2021 did end up making money by investing in stocks. This was a clear case of herd mentality proving to be beneficial for a good chunk of investors. Nonetheless, the timing was of great importance.

Those who entered the party late and are still invested are probably now sitting on losses or have made very little money for the risk they took on. But, of course, the major reason for stock prices falling over the last few months is the relentless selling carried out by foreign institutional investors (FIIs). Take a look at the following chart, which plots the net investment or selling carried out by FIIs during a particular month.

The FIIs have sold stocks worth Rs Rs 1,29,635 crore from the start of October to now. In fact, just between January and now, they have sold stocks worth Rs 91,114 crore. Despite this relentless selling, the Sensex has fallen by around 6.2% from the end of September. Of course, there are stocks and indices which have fallen much more.

The point is that stock prices haven’t fallen in line with the relentless selling by the FIIs. Oil prices have also gone through the roof in the last couple of weeks. Despite this, stock prices have been quite resilient. In fact, in a 4 March report, analysts at Morgan Stanley wrote: “Historically, India’s relative stock prices to emerging markets have reacted poorly to oil price increases caused by supply outages.” In simple English, this means that when the oil price goes up, Indian stocks fall more than other developing countries. But there seems to be a relatively calm right now, the analysts said.

They attribute this to multiple reasons, including policy certainty and the declining oil consumption relative to the Indian economy. But one reason on which enough emphasis hasn’t been put, and it gets lost in a whole host of reasons that have been offered for the relative calm, is the Indian retail investor.

As mentioned earlier, the Indian retail investors have been on a demat account opening spree. The total number of demat accounts as of January 2022 stood at 8.4 crore. Between the end of December 2019 and January 2022, a total of 4.46 crore demat accounts were opened. So, more than half of the demat accounts in India have been opened in a little over two years.

Interestingly, 3.42 crore demat accounts have been opened between the end of December 2020 and January 2022. This means more than 40% of the demat accounts in existence have been opened in the last 13 months. Further, 1.93 crore accounts or nearly one-fourth of the demat accounts in existence were opened between the end of July and the end of January, a period of six months.

These investors have invested a lot of money in stocks. There is no way of coming up with an exact estimate. Nonetheless, this money has been one reason why stock prices haven’t fallen, as much as they would have in a similar situation in the past when FIIs have been selling, and oil prices have moved up.

Also, retail investors invest in stocks through other avenues as well. Take the case of mutual funds. The money coming into mutual funds through systematic investment plans (SIPs) has simply exploded over the last few years.

A bulk of the money coming through the SIP route is invested into equity mutual funds. There are other ways in which retail money finds its way into stocks through insurance companies and pension and provident funds. For the investment carried out by mutual funds, insurance companies, pension and provident funds, banks, etc., we can look at total investment carried out by domestic institutional institutions (DIIs). Much of the money directly invested in stocks by such institutions is retail money.

The following chart plots the monthly net investment carried out by DIIs and FIIs since January 2020.

The above chart makes for very interesting reading. In the last six months, the FII curve and the DII curve have gone in opposite directions and look very similar. It’s the money being invested by DIIs which has ensured that the stock prices are relatively calm. What that means is what FIIs are selling, the DIIs are buying.

Using the philosophical tool Occam’s Razor, which states that the simplest explanation is usually the best one, in this case, one can safely say that the stock prices are relatively calm because of retail investors. Every other reason is essentially noise.

Now, as can be seen in the number of demat accounts data, retail investors take time to enter the market. More than 40% of the demat accounts were opened in 2021 and January 2022. This after stock prices had run up quite a bit in 2020. My feeling is that many such investors continue to be confident about investing in stocks.

Let’s try understanding this in some detail using what mathematicians refer to as the principle of induction. As David Foster Wallace writes in Everything and More-A Compact History of Infinity: “The principle of induction states that if something x has happened in certain particular circumstances n times in the past, we are justified in believing that the same circumstances will produce x on the (n+1)th occasion.”

Wallace then explains this in detail with the example of four chickens in a coop, with the brightest chicken being called Mr Chicken. As Wallace writes: “Every morning, the farm’s hired man’s appearance in the coop area with a certain burlap sack caused Mr Chicken to get excited and start doing warmup-pecks at the ground because he knew it was feeding time. It was always around the same time every morning, and Mr Chicken had figured out, (man + sack) = food.”

This is the principle of induction. If something is true n times, it will also be true the (n+1)th time. Given this, Mr Chicken was “confidently doing his warmup-pecks on that last Sunday morning”. At this point of time, the “hired man suddenly reached out and grabbed Mr Chicken and in one smooth motion wrung his neck and put him in the burlap sack and bore him off to the kitchen.”

So, what’s the lesson we can draw from this? As Wallace puts it: “The conclusion, abstract as it is, seems inescapable: what justifies our confidence in the principle of Induction is that it has always worked so well in the past, at least up to now.”

In that sense, retail investors work along similar lines. Only when they have seen stock prices go up for a while, do they believe that stock prices will go up further and start buying stocks. Like the chickens, they have the required evidence. They then assume that just because they have now bought stocks after the prices have gone up, the prices will continue to go up further. This explains why FIIs have been selling over the last six months, and the retail investors have continued to buy. Once the retail investor has bought into a story, it takes time to unravel. In fact, new retail investors continued to enter the market even in January when 34 lakh demat accounts were opened.

Take a look at the following chart. There are three elements in the chart: the net investment of FIIs during a year (on the left-hand side), the net investment of DIIs during a year (on the left-hand side) and the price to earnings ratio of the BSE Senex (on the right-hand side).

What does the chart tell us? It tells us that from 2010-11 to 2014-15, when the stocks were available at considerably cheaper valuations than they are today or have been over the last two years, the FIIs bought a lot of stocks. The cheaper valuation can be seen in the lower price to earnings ratio of Sensex stocks.

The price-to-earnings ratio is obtained by dividing the latest market price of a stock by the company’s earnings per share in the past 12 months. It’s the money investors are ready to pay as a price for every rupee of a company’s earning. So, if the price to earnings ratio is 20, investors are ready to pay 20 rupees for every rupee earned. And when it comes to the price-to-earnings ratio of the Sensex, it is the amount of money that investors are willing to pay as a price per rupee of earnings of the 30 stocks that constitute the index.

From 2010-11 to 2014-15, when stocks were available at lower valuations, the FIIs bought stocks worth Rs 4,84,930 crore. During the same period, DIIs sold stocks worth Rs 1,60,454 crore.

From 2015-16 to 2019-20, the price-to-earnings ratio of the Sensex index kept increasing, and the presence of the FIIs in the stock market was rather limited. Their total investment in stocks during the period was around Rs 73,231 crore. During the same period, DIIs bought stocks worth Rs 4,23,833 crore.

What does this tell us? It tells us when stocks were cheap (i.e. available at a lower price with respect to their earnings), DIIs (aka retail investors) were selling them. Further, the chart also tells us that the DIIs have been buying them when stocks have been expensive. This is exactly the opposite of the “buy low, sell high” investment strategy that experts keep talking about all the time.

Now let’s consider the time from 2020-21 on. In 2020-21, FIIs bought stocks worth Rs 2,74,032 crore. This was when stocks were more expensively priced than in the past. But the point to remember here is that this is the year rich-world central banks printed a lot of money and flooded the global financial system with it to drive down interest rates in the aftermath of the spread of the covid pandemic. FIIs were taking advantage of this.

The DIIs meanwhile sold stocks worth Rs 1,32,389 crore during the year.

In 2021-22, as stocks became even more expensively priced, FIIs have sold stocks worth Rs 1,29,027 crore. The DIIs, buoyed by the retail investors, have bought stocks worth about Rs 1,99,914 crore. Again, DIIs have bought stocks when they are expensively priced.

So, the story of the Indian stock market goes somewhat like this. FIIs buy stocks when they are cheap. DIIs (aka retail investors) buy stocks when they are expensive. This is basically because most retail investors invest once they have seen stock prices go up for a while.

This is herd mentality at work, and it sets up retail investors for a shock when the stock market falls as it has in the recent past. When that happens, retail investors are like the chicken up for slaughter but have been having a good time until then because it has been assumed that the future will be like the past and the present.

But that doesn’t always turn out to be the case. Confident dreams fed by herd mentality often depend on the timing, and money can be made if one gets in and gets out at the right moments. But many investors don’t. And then they are shattered.

In a way, such investors are like ants stuck in a circular mill. As James Surowiecki writes in The Wisdom of Crowds: “In the early part of the twentieth century, the American naturalist William Beebe came upon a strange sight in the Guyana jungle. A group of army ants was moving in a huge circle. The circle was 1,200 feet in circumference, and it took each ant two and a half hours to complete the loop. The ants went around and around the circle for two days until most of them dropped dead.”

This is the circular mill of ants. It happens when ants get separated from their colony and follow a simple rule of following the ant in front. This leads to the circular mill, which only breaks when a few ants straggle off by luck and the ants behind them follow.

This is what happens to retail investors who start investing because of herd mentality by imitating people around them. For a while, it looks like a logical decision and money is made. Then the stocks might fall, and the retail investors are saved only if they act like freak ants and break the circle and get out. Or if they decide to follow other retail investors who are breaking out. Of course, this is easier said than done, which is visible in the last chart.

In this scenario, many retail investors make losses or very little returns. As Surowiecki writes: “The simple tools that make ants so successful are also responsible for the demise of the ants who get trapped in the circular mill.”

The herd mentality school of investing is a tad like that. It works until it doesn’t.